For Anderson, YouTube illustrates the principle that Free removes the necessity of aesthetic judgment. (As he puts it, YouTube proves that “crap is in the eye of the beholder.”) But, in order to make money, YouTube has been obliged to pay for programs that aren’t crap. To recap: YouTube is a great example of Free, except that Free technology ends up not being Free because of the way consumers respond to Free, fatally compromising YouTube’s ability to make money around Free, and forcing it to retreat from the “abundance thinking” that lies at the heart of Free. Credit Suisse estimates that YouTube will lose close to half a billion dollars this year. If it were a bank, it would be eligible for TARP funds.

–Malcolm Gladwell, Priced to Sell

Gladwell’s must-read New Yorker review of Chris Anderson’s Free: The Future of a Radical Price nails its short-sighted, conference circuit talking point to the wall for anyone to see, so I was a bit surprised and disappointed when Seth Godin offered a rather weak defense of Anderson’s work, simply titled “Malcolm is wrong“.

I became a big fan of Godin’s after reading Tribes last year, and honestly, much of what I’ve been doing over the past 6+ months here on the blog, at work, and in my side pursuits was inspired by its underlying message of “be the change you want to see in the world.” Both in Tribes and on his blog, he tends to keep things simple without belaboring the obvious, but sometimes that simplicity can be a major flaw, as it is in his support of Anderson’s hyper-simplistic premise.

Ironically, he uses poetry as an example to prove his point, but ends up doing the exact opposite:

In a world of free, everyone can play.

This is huge. When there are thousands of people writing about something, many will be willing to do it for free (like poets) and some of them might even be really good (like some poets). There is no poetry shortage.

While it’s true there is no poetry shortage, quantitatively speaking, the “everyone can play” idea was the basic premise of the poetry slam which ultimately proved to be tragically flawed and a perfect case study for new media evangelists.

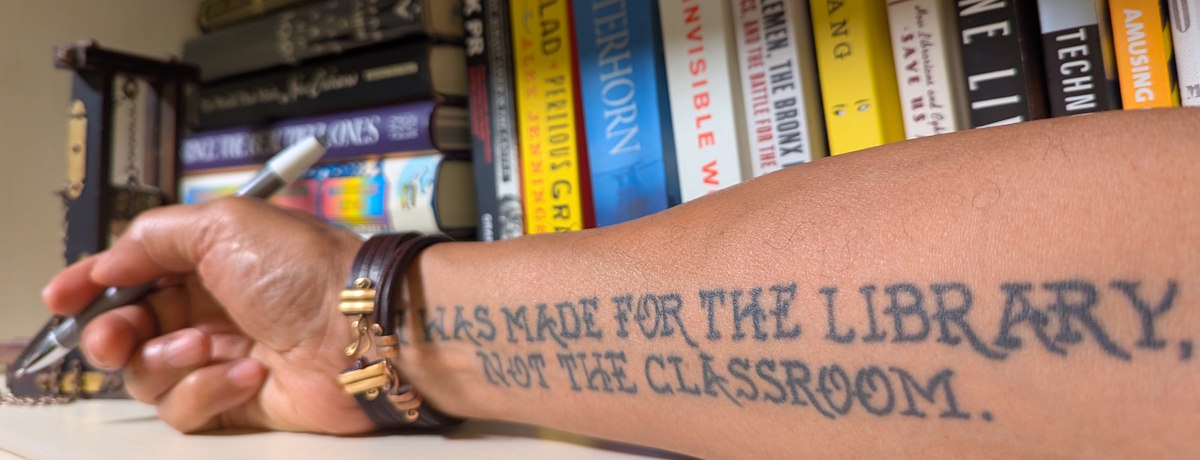

When I ran my weekly poetry series back in the late-90s, the least-attended nights were usually the free open mics, when the smaller audiences were predominantly poets looking for stage time. The best, most-attended nights had a cover charge and were a curated mix of featured poets plus an open mic that attracted both poets and non-poets. It’s a pattern I’ve seen remain consistent over the years here in New York City, and it’s one that’s not unique to poetry readings.

The reality is that those who believe the democratizing effects of the social web will bring about dramatic changes in the valuation of content are wrong, and in some self-serving cases, are simply being disingenuous:

“Gatekeeper” is a four-letter word on the publishing industry’s conference circuit these days, a straw boogeyman invoked to elicit visions of old white men in leather chairs dictating what the masses should and shouldn’t be reading. Who needs traditional publishers when the almighty (and ever-changing) algorithm and the “wisdom of the crowds” threaten to extract the soul from all content, leaving us with LOLCATS, Jon and Kate and Blogola? There will always be gatekeepers of one form or another, whether traditional publishers or the crowd-sourced variety. In both cases, the crowds are usually led by a few vocal minorities, and both have a history of chasing trends while ignoring new voices and ideas, so what’s old is basically new again.

The Economist, the darling of the Content is King faction in the magazine world, has a worldwide circulation of over 1.3 million readers, 75% of which is via paid subscriptions. A one-year subscription to the respected weekly is $126.99, and while other newsweeklies have watched their circulation and advertising revenues collapse, they’ve reported “profit is up 26 percent (to almost $92 million ) and revenue is up 17 percent (to $513 million) for the fiscal year ending on March 31.”

“These results demonstrate once again that great brands delivering real value to readers and advertisers thrive even when the economic cycle turns and when the structure of the industry is evolving in the way information and advertising are consumed and delivered,” CEO Andrew Rashbass said in the release.

Content + Context = Value — for both consumers and advertisers — and in today’s rapidly shifting media landscape, that equation represents survival for publishers.

I do agree with Anderson and Godin’s underlying point, the “freemium” model — giving away some content while offering a more valuable experience for a premium — but it’s neither a new idea nor a terribly innovative one. Take a walk through Costco any Saturday and you’ll sample a variety of items they’re trying to entice you to buy, from crab dip to fancy chocolates; it’s a model drug dealers have perfected, both legitimate and illegal.

In fact, it’s the very model Anderson and Godin are both profiting very nicely from with their own work, leveraging their respective online platforms (and in Anderson’s case, his employer’s print platform) into lucrative, and ironically traditional, book deals and speaking gigs.

Of course, a freemium platform’s success is ultimately contingent on the quality and credibility of the content, starting with the free samples.

Based on the FREE samples Anderson has offered in interviews and at conferences, it’s not something I’d pay for because it doesn’t appear to add anything of value to the discussion; I’d argue he’s actually going the more traditional route, and extracting value from the discussion for his own gain.

Malcolm Gladwell FTW!

[UPDATE]: Andrew Keen, outspoken author of The Cult of the Amateur: How Today’s Internet is Killing Our Culture, sides with Gladwell on Twitter:

- Godin wrong.: “In a world of free, everyone can play.” Yes, but in world of free, 99% of people lose. Las Vegas rules. #

- winners in free economy are clever marketers like Godin, Anderson & myself. Neither fair nor fruitiful. Cheapening rather than enrichening. #

- annoying about Gladwell review of Free: he’s decimated argument so cleverly that there’s nothing else to say. What can I write in my review? #

Seth Godin is also tracking “The FREE Debate” over at Squidoo, including Anderson’s specious and evasive response to Gladwell’s review, “Dear Malcolm: Why so threatened?” that’s getting some very interesting comments. While this is heading into #EPICFAIL territory for Anderson, it likely won’t affect his book sales much, nor his speaking gigs.

As Godin notes, “Part of what Chris, Malcolm and I do for a living is make sweeping, provocative statements that don’t always include every nuance.” Sweeping, provocative statements lacking nuance are the lifeblood of both the conference circuit and real-time media.

Do you like email?

Sign up here to get my bi-weekly "newsletter" and/or receive every new blog post delivered right to your inbox. (Burner emails are fine. I get it!)

I think the counter examples (like the Economist) highlight the astonishing changes that are going on (which starts with writing, but moves from there). It's easy to forget that just ten years ago, doing what you and I are doing right now was essentially impossible.

The next generation of consumers can't imagine paying for a newspaper (subscriptions by 25 year olds are a tiny fraction of what they were for 25 year olds a decade ago) or a CD. Sure, I'm happy to pay (I pay for several newspapers a day) but is that the future?

Editors are important, as I said. If you're paying for poetry, that's almost certainly what you're paying for, right?

Seth, the containers may change and get cheaper, but it's the content that gives them value, and the creation and distribution of quality content isn't free. Traditional publishers will have to transform because technology forces reinvention, but as you note, editors are important and curated content has more value than a chaotic free-for-all.

The internet may ultimately be cheaper than print, but the myth of “free” is part of the reason so many publishers are feeling the pain right now, thanks to illogical digital investments that are never going to pay off. (Many still believe email is free; it's not!) Will most newspapers disappear in the next 5-10 years? Probably; but so will the vast majority of websites, along with the vast majority of wannabe writers who think WordPress can turn them into the next Seth Godin.

Thanks for stopping by with a comment. I remain a fan!

PS: While you were commenting, I was tweaking the post a bit, including changing the Gladwell excerpt in the intro. Nothing significant, but wanted to make sure to point it out.

Guy, I love the comparison to your poetry slam series. I just witnessed a very similar dynamic with the open submissions Flash Fiction 40 Contest I just ran on Editor Unleashed. Allowing open submissions and a popular vote led to chaos and mayhem (although it should be noted, I was impressed that the popular vote did pick some of the best stories).

I asked for feedback after and many requested anonymity, a closed submissions process, and a less transparent ranking system if there was one at all. Many also noted they didn't have time to sort through all of the slush. In other words, back to old school! I don't truly think the world (at least the world of writers) is as ready, willing or able for a new transparent world of publishing as many would like to believe.

The drama in the poetry slam scene was/is ridiculous. “Everybody can play” evolved into many sub-par “poets” becoming the most popular because they gamed the system, appealing to the lowest common denominator and delivering flashier performances. Kind of live action SEO! And the power struggles? Imagine a bunch of goldfish in a Mason Jar fighting for control. The future, indeed.

Keen nailed it in his tweet: “winners in free economy are clever marketers like Godin, Anderson & myself. Neither fair nor fruitiful. Cheapening rather than enrichening.”

This continues to strike me as the difference between design — whether its a game or a government — and the utter mess of true free-form behavior. Free verse works because it still has the design of the language to use, but while total chaos may result in a culture it probably won't result in a civilization. We want a civilization, don't we?

Wherever the rules and systems come from that determine what's Free and who gets paid, there will be rules. Free, after all, is a price, not a value. Something that is Free and worth little or nothing gets left on the freebie table (or in the trash, or on the floor). The value is getting something for Free is often in the *savings* — the fact that it's worth, usually to the consumer, much more than was paid. That worth has to come from somewhere.

Agreed; “free” still has to have a definable value or else it's worthless. In the freemium model it's the teaser; if freebie has no real value, there's no conversion. That applies whether it's a free sample of chocolate; a free issue of a magazine; or the freely available article that begat FREE in the first place (http://bit.ly/6c0YQ).

At least one thing we can all agree on. This debate hit the nerve. I am glad that I am not alone in my sentiments though.

Let me just say that the Long Tail remained a nice theory.

I thought Malcolm was spot-on and I don't always agree w/ his reasoning or examples … I thought he was at his best in reviewing hte book as he provided “real” examples vs. pontificating around hypotheticals … there is so much junk out there today … unresearched, undocumented, non-evidenced … I have heard people quoting stats they read off a blog that are so off-base as to be comical (not to be dichotomous – there is some MSM stuff that is of poor quality as well – and blogs that are fantastic, but …) … the antipode here is that “you get what you pay for” … which, may not always be true, but is still alive in the content world as well … I think the free model has a place (see versioning, LinkedIn model, etc.), but it's not the whole model … at the end of the day, none of us are free anyway – we all make tradeoffs around liberty vs. security (e.g., zoning) and willingly sacrifice freedom for more important goals – info is no different.

The Economist is less interesting than people claim. Yep, it's doing well. But that's because a/ it's a 'specialist' publication (quite a few specialist/niche publications are still doing well) and b/ because it's a specialist publication specifically aimed at a class of older wealthy men for whom the price is insignificant and probably tax-deductable (if it's not paid for by the company.)

Good on them. Certainly they provide some quality content. (How's the WSJ doing…?) But as a general model for the future of on-line media- unconvincing. (I'd like to think a brilliantly well-edited website for, eg, terrific short-stories, could also run a subscription model. But then you can get much of that for free at the New Yorker site.)

Advocates of “free” love vague pronouncements because real-world examples are limited to models that benefit initial investors and select middlemen, or hobbyists. There's no “economy” there. There's an interesting debate over on Fred Wilson's blog about it, to which Ben Atlas has contributed some smart comments: http://bit.ly/E3Fxf

The Economist is profitable, which is why is referenced so often. Even in the ad-supported land of “free” online, there are far more niche success stories than there are those working off the old network TV model of maximum eyeballs. The common denominator: quality content that's worth paying for.

While the debate around it is valuable, FREE is just another flimsy theory to keep the speaking fees coming once Anderson was forced to admit “It’s hard to make money in the [Long] Tail.” http://bit.ly/q43zZ

It seem that everyone who have spoken and this debate, all use one note that justifies the way they do things. This is a loud debate but it lacks rigor and not a single person gives any impression that they know how things will unfold. All they do is hold for dear life to the money making post they planted in the space.

Guy, I, too, am disappointed. The communication industry needs thought leaders who are interested in improving value. Mass media has responded to increased competition for audience by seeking the lowest common denominator. As Leo Burnett said – 'anyone can get your attention by walking in a room with a sock in their mouth.' The idea that new technology should be used to perpetuate the race to the bottom is just saying what so many hope is still true – “you don't have to give up on 'lightening in a bottle.'”

The truth is there are more profitable possibilities. Subscriptions to premium channels grew to new record highs in 4th quarter 2008 while consumers were finally informed of the economic collapse that had been threatening for over a year. Consumers will pay for value. They know you get what you pay for.

Contrary to Anderson's opinion that the Monty Python example demonstrates the power of free, I think it demonstrates that there is an opportunity to drive up the sales of a “Long Tail” brand to #2 sales on Amazon by reaching out to your fans. Sure they got a list of fans from YouTube. But there's lots of ways to engage fans to give you their names. Free is by no means the only or the best way.

Sincerely, Katherine Warman Kern

Children – here’s a new thought for you – first of all – the free thing is not new – in the 60’s we had free love – free drugs and what did it get us – revolutionaries in suites and dogma – so, lets move on to new toys – most of the art is a rehash – there are new waves of thought coming – 3D writing – art of expression – belief in now – maybe your grandchildren will understand – by the way, this is not suppose to make sense – your brain and attitudes are not ready for it.